The strain of E. coli linked to McDonald’s Quarter Pounders is one of the leading causes of foodborne illness in the U.S.

On Oct. 22, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that an outbreak of the bacterial infection had sickened at least 49 people in 10 states. One person has died.

While there are many types of harmless E. coli, there are six that can cause diarrhea, including O157:H7, which may have contaminated raw onions used on the burgers, according to federal health officials.

Here’s what to know about staying safe from E. coli.

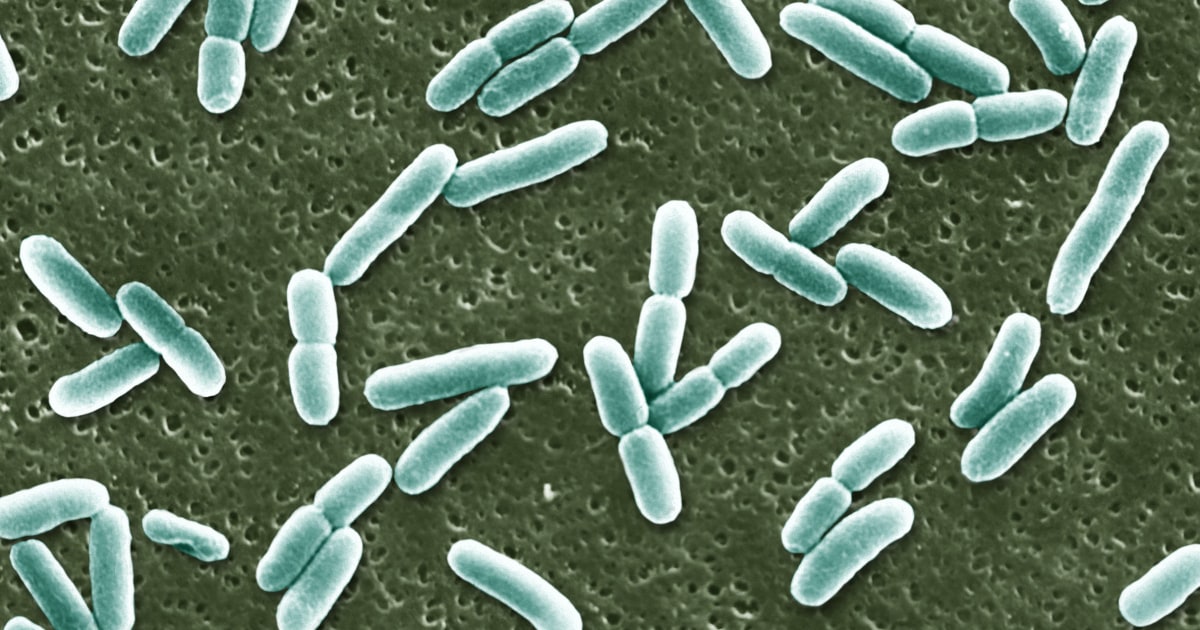

What is E. coli?

Escherichia coli is a type of bacteria that spreads in feces and can contaminate food, potentially causing serious infection.

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) is the most common type in high-income countries, like the U.S. It’s the type of E. coli that has been implicated in the McDonald’s outbreak.

Although STEC infection most severely affects children younger than 5 years old and adults aged 65 and older, anyone can be infected.

“This one is the dying kind,” said Prashant Singh, a food safety microbiologist at Florida State University, stressing the danger of this type of E. coli.

According to the CDC, symptoms commonly include bloody diarrhea, severe stomach cramps and vomiting. In vulnerable groups, E. coli infection can also lead to serious kidney complications and death.

People can become infected after consuming contaminated food or water, or coming into contact with the feces of animals or infected people.

What are the symptoms of E. coli?

E. coli symptoms usually show up three to four days after ingesting the bacteria, but it may take up to 10 days.

Once inside a patient, the E. coli stick to the inside of the intestines and produce a toxin that kills the cells lining the gut. This causes inflammation of the intestines, leading to watery diarrhea that becomes bloody after one to three days. Low-grade fever is also a possible symptom.

The severe diarrhea and intestinal inflammation can lead to dehydration and abdominal tenderness. In vulnerable patients, severe infection can lead to death.

The O157:H7 strain can also cause a very dangerous complication called hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which involves damage to the blood vessels, leading to red blood cell destruction and kidney injury. The cells involved in blood clotting are also destroyed, leading to easy bruising. Symptoms of HUS range from blood in the urine and swelling of the legs, all the way up to seizures and death.

While it mostly occurs in children, anyone can develop HUS.

How does E. coli get into food?

Despite improvements in surveillance and technology to identify them, foodborne outbreaks can still be difficult to catch quickly, said Barbara Kowalcyk, director of the Institute for Food Safety and Nutrition Security at George Washington University Milken Institute School Public Health.

That’s because most people who are sickened don’t go to a physician. And of those who do, days or weeks might pass from the time of their contamination to the time that a pathogen such as E. coli is identified — especially because symptoms might not have started immediately.

“The doctor may order a stool sample, they may wait a couple more days to order a stool sample,” Kowalcyk said. “The lab tests it. It takes a day to get the test result back. Then if it’s positive, then they contact the health department, and then the health department contacts you and says, ‘What did you eat two weeks ago?’”

Still, manufacturers have done a lot to reduce contamination, she said, particularly in foods such as ground beef — something that is personal to Kowalcyk. Her 2-year-old son Kevin died in 2001 from complications of E. coli after he ate what the family believes had been a contaminated hamburger.

“There’s a lot of people that are doing work on, how do we build positive food safety culture into food companies so that they don’t cut corners, when there’s a lot of pressure to cut corners?” she said.

“Typically, E. coli is associated with cattle, but it’s been found in a variety of other fruit and vegetable products as well,” said Donald Schaffner, a distinguished professor, extension specialist and chair of the Department of Food Science at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Schaffner formerly served as a member of the McDonald’s Food Safety Advisory Council.

The O157:H7 strain is classically known to be associated with the ground beef in hamburgers, with the bug usually residing in the intestines of animals like cattle.

In the case of beef, the bacteria “could have been in the intestines of the animal and then, during the slaughter operation, sometimes those intestines are accidentally cut, and that can lead to getting pathogenic E. coli on the cuts of beef, and then it goes through grinding and ends up in the ground beef,” Schaffner said.

If it’s a contaminated vegetable, like onions, “it could be that the onions are being raised in a field that’s close to a cattle operation, and the E. coli blew in from the cattle operation. Or, maybe in that field, they use cattle manure as compost,” said Schaffner.

One of the largest outbreaks caused by this strain was linked to spinach and traced back to fields in California, which were near a cattle farm. That 2006 outbreak sickened 205 people and caused three deaths.

If fruits and vegetables aren’t properly cleaned, they could remain contaminated. Or they could become contaminated later, during processing.

For example, infected individuals who don’t practice appropriate handwashing after using the bathroom could spread the bacteria through retained fecal matter on their hands. Likewise, after changing the diaper of an infected child, E. coli in the fecal matter could spread to food.

Once the contaminated food enters the kitchen, it’s also possible for cross-contamination to occur if ingredients are mixed or handled improperly.

Because E. coli is found in cow intestines, unpasteurized dairy products can also carry the bacteria. Likewise, unpasteurized fruit juices may carry the bug if they were produced from contaminated produce.

There are other ways to become infected with E. coli outside of food, as well. Untreated water may carry E. coli. Pool water may also carry the bacteria if an infected person recently swam in the pool.

E. coli can be spread by individuals through contact with their feces. People who don’t wash their hands after using the bathroom can pass on the bacteria to surfaces or directly to other people, as well.

How to avoid E. coli infection

The first step to steering clear of infection is avoiding food that is known to be contaminated.

Seventy percent of foodborne outbreaks or infections happens from eating out, not at home, said Singh, recommending that people depend on home cooking as a less likely source of infection.

When you are eating food prepared by someone else, you can feel more confident when the food has been thoroughly heated to an internal temperature of over 160 degrees F, which kills E. coli.

Refrain from consuming unpasteurized dairy and juices, as they may be tainted.

Good hygiene is the cornerstone of preventing E. coli spread. Proper handwashing by anyone preparing food is crucial to stopping the transmission of the bacteria.

If you are experiencing diarrhea, don’t swim in a public pool to minimize the risk of transmission. If you swim in untreated water, refrain from swallowing.

Overall, E. coli is a dangerous kind of bacteria that should be taken seriously, especially by vulnerable groups. Proper precautions can help to reduce the spread.

If you do become infected, it’s important to swiftly seek medical attention to stave off more serious complications.

Leave a Reply