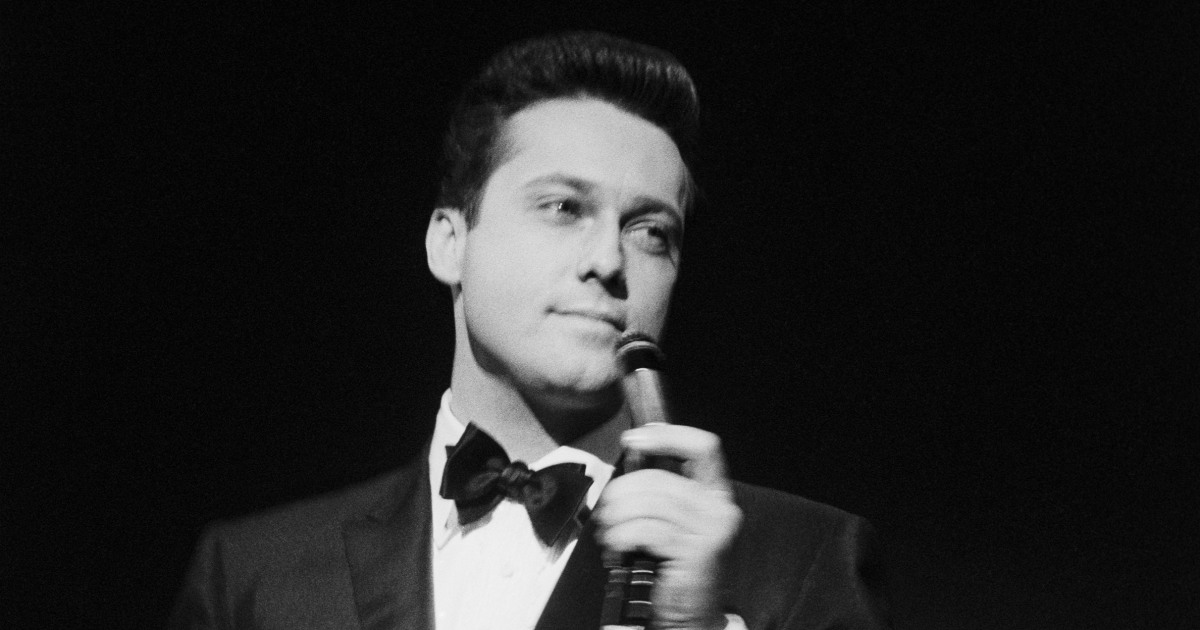

Jack Jones, a singer who found fame and chart success on the easy-listening side of the street in the 1960s, and who later became etched in television-watching America’s psyche with the “Love Boat” theme, died Wednesday at 86.

Jones died of leukemia at a hospital in Rancho Mirage, Calif., his wife of 15 years, Eleanora Jones, said.

Jones had hits on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, but his highest chart numbers could be found on what was then known as the easy listening chart, which later became adult contemporary. In the easy listening format, he had No. 1 singles with “The Race is On” in 1965, “The Impossible Dream (The Quest)” in 1966 and “Lady” in 1967.

In particular, “The Impossible Dream” — a cover of the most popular song from the 1965 Broadway musical “Man of La Mancha” — became culturally ubiquitous, through Jones’ frequent TV appearances, even though it peaked at No. 35 on the Hot 100, where it had to compete against more clearly youthful fare. As it continued to be a staple of his live performances over the decades, Stephen Holden of the New York Times wrote that his rendition of what had become a standard “transforms this sentimental war horse into an anthem of personal determination, not only to keep moving, but to get better.”

The “Love Boat” theme was heard by millions of Americans every week during that show’s 1977-86 run on ABC. Jones spoofed the song’s old-fashioned appeal — and his own — by singing it in a cameo as a lounge singer in the 1982 comedy “Airplane II.”

Even in the ’60s, Jones’ appeal was seen as old-school — which helped endear him to an America that was not yet ready to completely trade the Frank Sinatra wing of pop music for the British Invasion, and to producers of TV variety shows who understood that a Jones appearance provided a kind of comfort food for audiences as times and styles changed.

His songs could still be used in the present day to evoke an era — as when “Mad Men” used “Lollipops and Roses” as an end-credits theme.

But his appeal was not all about nostalgia, or kitsch — Jones was respected by students of the so-called crooner era. Reviewing him in the Wall Street Journal in 2012, classic-vocalist expert Will Friedwald wrote, “It isn’t the pure power of his voice that is most impressive. It’s the sensitivity with which he animates a lyric, a sensitivity that only increases with age.”

“As my career gained momentum,” Jones said, “I developed a deep appreciation for well-constructed songs with emotional appeal. I was influenced by the great balladeers — Sammy Cahn, Jimmy Van Heusen, Cole Porter, the Gershwins, Harold Arlen, Michel LeGrand, and Alan and Marilyn Bergman, as well as instrumentalists including Gerry Mulligan, Buddy Rich and Count Basie.”

Jones considered himself an actor as much as singer, although he didn’t pursue the screen as ardently as he did recordings. His films include a pre-stardom appearance in the 1959 musical “Juke Box Rhythm” and a leading role in a 1978 slasher film, “The Comeback,” in which he played a singer tormented by a killer. More often he was seen on the touring musical-theater circuit, doing shows like “Guys and Dolls,” “The Pajama Game” and — of course — “Man of La Mancha.” He had a cameo in David O. Russell’s “American Hustle” in 2013, singing the Cy Coleman number “I’ve Got Your Number.”

Jones was the son of actors Irene Harvey and Allen Jones, the latter of whom who appeared in the Marx Brothers films “A Night at the Opera” and “A Day at the Races.” “My father hit actual movie stardom in 1938, and that was because Jeanette McDonald and Nelson Eddy were together so much that MGM decided they wanted to break them up a little bit (and not) have Nelson Eddy in (a film),” Jones recounted. “They brought my father in, and it was called ‘The Firefly.’ The song, ‘Donkey Serenade,’ that was in that picture became a tremendous hit… He recorded it the night that I was born in 1938. You’re taking to a fossil,” Jones quipped.

Jones was briefly part of a family act with his parents. He attended University High School in West Los Angeles, where his friend Nancy Sinatra is said to have invited her father to sing in the school auditorium, so impressing Jones that he determined to follow in Frank Sinatra’s footsteps.

His first recording efforts in the late 1950s included a stint recording rockabilly-styled songs for Capitol Records, an approach he said was forced on him. A subsequent affiliation with Kapp Records led to “Lollipops and Roses” — recorded while he was on leave from the U.S. Air Force Reserve — establishing his career. Although it only reached No. 6 on the easy listening chart and No. 66 on the Hot 100, the song had staying power and won him a 1962 Grammy for best male solo vocal performance.

His second Grammy came in the same category in 1964 for “Wives and Lovers,” a future standard written by the hit team of Burt Bacharach and Hal David. It was also nominated for, but lost, the record of the year competition. “Wives and Lovers” peaked at No. 9 on the easy listening chart, but perhaps tellingly in regard to its popularity, it marked his high point on the Hot 100, making it to No. 14. Although the song was accused by some of having sexist lyrics, it continues to enjoy popularity today among jazz singers like Cécile McLorin Salvant.

The last of Jones’ four Grammy nominations came in 1998 in the traditional pop vocal performance category for his album “Jack Jones Paints a Tribute to Tony Bennett.” Altogether, Jones released 60 albums.

Jones kept up his smooth tone over the decades, and credited one decision in particular for that longevity. “If I hadn’t stopped smoking about 40 years ago, I wouldn’t be singing, let alone being alive,” he said in a 2016 interview with Las Vegas magazine. “It’s the worst thing you can do to your voice, so I’m very grateful that whatever it was that made me want to quit, that I went through with it.”

Reviewing a Jones performance at the Algonquin Hotel in 2008, the Times’ Holden noted, “Mr. Jones has a healthy sense of humor. Reflecting on the ‘Love Boat Theme,’ he joked that he had made of millions of dollars by threatening to sing it. Then he did. It wasn’t so bad.” But Holden had greater praise for his other material. “His weathered voice is filled with seams and crevices. It is the voice of a gentleman rancher astride a horse, surveying his property in a television western,” the Times wrote. “It is said that as we age, we become more and more ourselves. And the mature Jack Jones has refined a style that could never be called cookie-cutter… His world-weary cragginess coincides with an impulse to take ballads at extremely slow tempos and to execute them with the hesitations, drawn-out notes and sudden leaps that are a trademark of the jazz singer Mark Murphy. Because the lower end of Mr. Jones’s voice has deepened, his sudden flights into a quasi-falsetto are more dramatic than ever. At times they suggest the spontaneous eruptions of a polished stylist impatiently throwing caution to the wind.”

In his later years, Jones was a proponent of living in the Coachella Valley. “I love the palm trees, the sand, the open feeling. There is so much serenity,” he said.” I loved being against the mountains in Palm Springs as a youth, and still enjoy the changing colors of the mountains. We have the best of all worlds here.”

Jones was bestowed in 2003 with a star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars, joining the star he had gotten in 1989 on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Before wedding Eleanora Jung in 2009, Jones was married and divorced five times, including a union with actress Jill St. John.

Besides Jones’ wife, his survivors include daughters Crystal Jones and Nicole Ramasco, stepdaughters Nicole Whitty and Colette Peters, and three grandchildren.

Leave a Reply